You’ve likely been told, perhaps far too often already, that homeownership is the path towards “wealth generation”—here’s why I don’t share that belief.

Perhaps it is because I have yet to make a big-money score, and consequently, I can’t afford any reasonable piece of real estate.

Maybe it’s the fact that I’m already 35, and to me, a 30-year loan on a shoebox located an hour’s drive away from the city doesn’t smell like the deal of a lifetime.

Or maybe it’s because I’ve spent far too much time around construction sites and have become irreversibly jaded with the machinations of property developers.

For me, at least, it’s a combination of all the above. For economic reasons, I can’t purchase a home—and even if I could somehow scrape enough together to afford the luxury of owning my own home, for various other reasons, I wouldn’t.

Because Math

Anyone who has sat through an economics class might recall terms like supply and demand—and at least on a basic level, that’s all you really need to explain how we arrived at the present circumstances.

Homes Are Too Expensive

People move to the city because that’s where we stand the best chance of finding gainful employment. But because everyone wants to live in the city, there’s greater demand for space rubbing up against the inconvenient fact that there’s less of it to go around—and because there are more people wanting a home in the city (demand), and with each want fulfilled there is less space available (supply), prices inevitably go up.

I Don’t Earn Enough

There are plenty of reasons, having almost as much to do with land rights as well as economics, why real estate values in the city get higher and increase faster than the rest of the country, but we won’t go into that here.

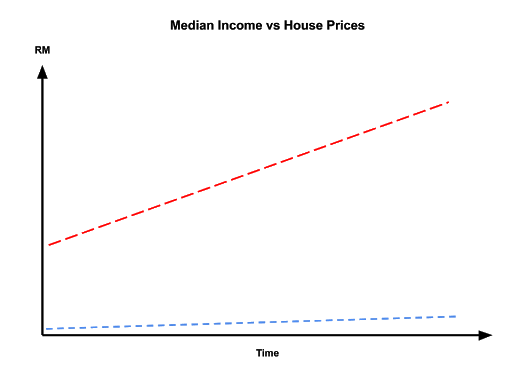

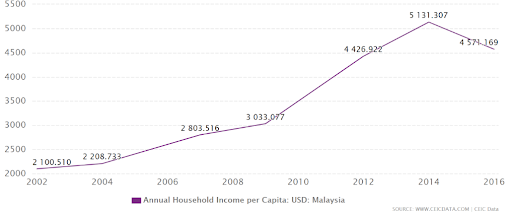

Assuming that you live in a perfect world where conveniently located housing is equally available to every living person, there is still the problem of a widening gap between what you earn and what a home costs.

Guess which is which

Depending on your qualifications and the industry you are in, your income puts you somewhere around that blue line hugging the axis labelled “Time”. Further up, and going stratospheric like a rocket, is the price of a home rising over time (on the red line).

While your income flies relatively lazily over the terrain, if you’re unlucky, inflation would be that predatory raptor swooping somewhere above your income.

That’s Inflation with a bit of Income in its beak. Photo by Jack Seeds on Unsplash.

Our Circumstances Differ

By this point of the avian-themed Economics 101 lecture, Boomer has probably run out of patience and will flippantly suggest that you work harder in order to earn more. This is when I would whip out the other half of my economic reasoning for rejecting homeownership.

Sometime in the past, when Boomer was fresh out of university ("OK, fine, you left school at age 12 to start a business”), that gap between housing prices and income was considerably smaller. Even after paying off the bills, there was likely some money left over at the end of the month to put towards a home loan—we know this because Boomer is retired and owns real estate.

Thanks to things like inflation—a natural feature of the largely democratic and free-market global economy that Boomer probably fought for—some of us will still be paying off our student loans when (if) we retire.

Perhaps by then, my “House Fund” jar might even be full. Photo by Sandy Millar on Unsplash.

There’s a reason the minimum retirement age has been raised—and it’s not because retirees sometimes get bored. Bean counters operating in fields ranging from insurance to policymaking have already projected that with the global money supply flying off the rails, we won’t be able to afford retirement, let alone satisfy any of our expected financial obligations, by age 55.

The simple(st) explanation for that: Because there is more money going around, it is worth less. Surprise!

Even without Frappucinos in the equation, some of us struggle just to keep our heads above water from month to month—which, incidentally, is the same reason why many of us are skipping past parenthood.

Besides inflation, there’s the half-century or so of planned obsolescence and a global throw-away culture that has our cars (and anything manufactured) purchased at higher prices and disposed of more frequently. Also, coping with the environmental costs of all that has become a bit inconvenient.

We can definitively state beyond any reasonable doubt: None of that junk is ours. Photo by Camille Villanueva on Unsplash.

Stop Complaining Already

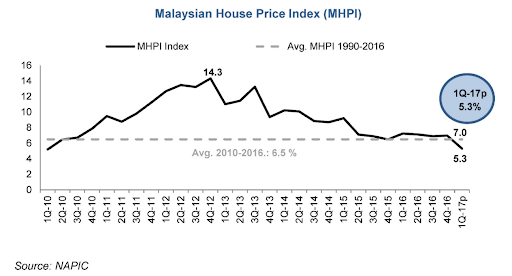

Glossing over the assertion that one generation’s circumstances may have adversely affected another’s, Boomer might point out that you could take a look at the declining Malaysian House Price Index (MHPI) and conclude that prices are rising slower than they used to.

Yes, for the first time in almost a decade, housing price increases are (almost, but not quite) on par with income increases.

But it’s not like we can stop worrying about climate change if we started capturing almost as much carbon as we’ve been putting out. Short of aliens invading, or some sort of global Project Mayhem, that widening gap between income and housing prices will not be narrowing anytime soon.

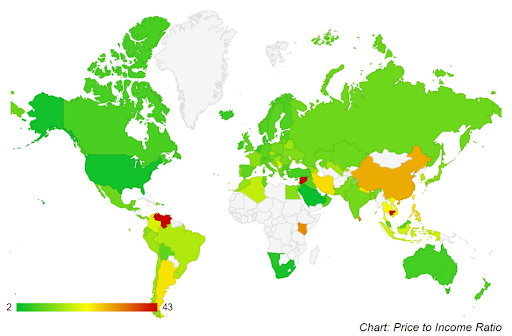

Boomer might even compare the ratio of house prices to income around the world to paint a “be happy with what you have” picture using a relatively high standing in comparison to places like Venezuela, Syria, Cambodia, or Hong Kong.

Ratio of House Price to Income Around the World in 2020

Sure, living here is (probably) better than living there.

There are various ways of looking at income, inflation, housing prices, or the relationships that bind them, to paint any picture you want. But these still-life comparisons between differing circumstances will not necessarily reveal our futures.

It’s difficult to deny the possibility that in some parts of the world, perhaps even in a different time, we could enjoy better access to housing, job opportunities, and social services. But migration might not magically turn those dreams into reality. There are places that are better off, and some others that are not—at least for right now.

Better and Worse Circumstances Are Unfolding Everywhere

Take Hong Kong as an example. The 2019 extradition bill may have been the trigger, but ask any concerned citizen on the street and they’ll tell you that the root cause of the unrest plaguing Hong Kong has been the many decades of unchecked property development for profit.

Even before the failed Umbrella Revolution of 2014, Hong Kong was notorious for being one of the world’s most expensive places to live. Unlike Singapore, where nearly every aspect of ordinary life is carefully gauged and controlled by the government in order to ensure the equitable distribution of resources, Hong Kong’s situation—or at least the start of it—can be traced back to profiteering by an oligopoly of business elite that still silently benefits from skyrocketing real estate values in the former British colony.

If I owned some of this landscape, I would be pretty quiet about it too. Photo by Ryan McManimie on Unsplash.

While Scandinavian children can consider skipping school in order to draw attention towards the dilemma of accelerated climate change, young adults in Hong Kong continue to struggle against free-market ideals run amok just to survive and live out a dignified existence.

Faced with the loss of their economic relevance, the youth of Hong Kong exploded when presented with further (perhaps perceived) reductions of their liberties in the extradition bill. Their reactions are more or less understandable when we consider that not only were they becoming economically powerless, the democracy that they grew up with was being dismantled.

Fortunately, we still enjoy a relatively stable and intact democracy, and our economy has some controls in place for the sake of social welfare. Otherwise, we would have to ask ourselves: How should we react to infringements on our own economic and political relevance?

I would probably go on some sort of beach holiday to de-stress. Photo by Tim Gouw on Unsplash.

Our Circumstances Are Either Comparable or Not

If our circumstances are unique, then we pretty much have carte blanche to fearlessly create our own solutions and shape our own futures. Our unprecedented range of possible options might include: -

1. Buckling up and doing our best to rise above the present situation;

2. Adapting to the present circumstances by accepting a lifetime of tenancy;

3. Affecting change by becoming politically involved and attempting to inject some equitability into our circumstances—which is no longer a sarcastic retort in this day and age; or

4. Disrupting the status quo by partaking in mass civil disobedience—which many people around the world are choosing to do.

On the other hand, if our situations are comparable, perhaps even identical, then these comparisons between historical and present circumstances are valid starting points to begin understanding our reality and discovering exactly what needs to be done in the name of rectification, equalisation, or even empowerment.

So, Why Can’t I Afford Real Estate?

Because I can’t possibly make enough money without perpetuating the cycle of economic servitude at someone else’s expense, and because we’ve all got deeper concerns than having our names on a land title.

Kevin Eichenberger has kept a “House Fund” jar since 1999—and it’s still mostly empty.

(Written by Kevin Eichenberger, 13th February 2020)